By Stan Solomillo

In 2007, a popular blog, “Sardonic Sistah Says,” noted that the resolution of the romantic interest between the late Aaliyah and Jet Li in the film Romeo Must Die (2000) ended up on the cutting room floor because in test screenings with “urban” audiences, the viewers did not approve of the kiss in the final scene. Unfortunately for the audiences (as well as Warner Brothers), in real life, there is a history of inter-marriage between African or African American women and Chinese men in the Americas that dates back to at least the nineteenth century as well as in the Mississippi Delta during and after Reconstruction (1866-1877).

Following the end of the Civil War, various immigration schemes were developed by Euro American business interests to employ Chinese contract laborers instead of newly freed African American slaves. They were hired for a number of endeavors including building railroads, felling forests, draining swamps, and cultivating rice, sugarcane, tobacco, and cotton.

Chinese laborers were initially classified as “Negro,” and arrived from Southern China (Guangdong Province), the Philippines, Cuba and other Caribbean islands, as well as New York, Philadelphia, and California. Brought under the auspices of Euro American and Chinese contracting companies or individual labor agents, they proved to be hard workers but were far from docile. Many left the fields as soon as the terms of their contracts were either completed or arbitrarily changed by an employer as well as for non-payment. This prompted such endeavors to be regarded as complete failures.

Chinese workers opted to either out-migrate from the South altogether, continue to work as individual contractors (including sharecroppers), or pool their resources to establish small businesses—mostly groceries—locating them in isolated African American enclaves in the Delta. This created two cohorts of Chinese—one rural and one urban. A majority of the rural Chinese appear to have married while the storeowners are purported to have largely remained bachelors (which has not been thoroughly investigated). Of those who married, the Chinese identities of the rural cohort were lost through successive generations by the changing of surnames and by census takers who altered racial classifications, while the identities of storekeepers remained largely intact.

The marriage partners of Chinese in the Delta appear to have been initially diverse. In Louisiana, the 1880 census recorded 489 Chinese in the state, of which 16 had married African American women (“4 Mulatto and 12 Negro”), 1 had married Chinese American, and 8 had married Euro American. In Mississippi, the census of the same year enumerated only 51 Chinese and unfortunately, detailed marriage statistics are not readily available. In addition, comparable analyses of the census data from later years remain only remotely accessible, which precludes an accurate enumeration of Chinese and African American inter-racial marriages, common law arrangements, and the bi-racial children born to those couples. However, one researcher estimated the former to number between 20-30 percent of all Delta Chinese out-marriages by 1920.

The trend in Chinese and African American inter-racial marriages in the urban cohort appears to have ended during the 1920s when American-born Chinese women and Chinese merchant families (who later came to be identified as “pure Chinese”) entered the Delta from source areas outside the region such as Chicago, New York, or San Francisco. (Their numbers increased slightly after WW II, following the1943 repeal of the Chinese Exclusion laws). Many in-migrating Chinese families had school-aged children.

The first formal attempt to integrate all-white schools in Mississippi through the admission of Chinese American students was initiated in 1924 when the daughter of Gong Lum, a Chinese grocer, was sent home from Rosedale Consolidated High School because she was not white. Litigation was filed by the family, styled Gong Lum v. Rice, and the case heard by the Mississippi Supreme Court which ruled that “Chinese [were] not white and must fall under the heading [of] colored races.” On appeal, the decision was later upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court on November 21, 1927. This prompted urban Delta Chinese to establish their own schools, often with the assistance of Southern Baptist churches, whose white congregations mandated that the student bodies remain “pure Chinese” and preclude the attendance of Afro-Chinese students.

From the 1970s onward, academic studies of the Delta Chinese by Loewen (1971), Quan (1982), and Cohen (1984) documented a transformation from recognition of inter-racial Chinese and African American marriages and their Afro-Chinese children to outright denial. One elderly Chinese woman in Mississippi who chose to remain anonymous stated to San Francisco researcher Robert Seto Quan that: “There was [sic] just a few Chinese men who took Lo Mok [African American] wives but we didn’t have anything to do with them. In our tradition, we don’t go for mixed marriages.” Her statements suggested an assimilation of prejudices from the majority white community and contrasted with those of a contemporary bi-racial descendent of a Chinese laborer who married an African American woman in Louisiana. Opting to remain unidentified as well, she recalled in an interview with Cohen that, “[t]hey [Chinese] married all kinds of people…Creoles, blacks, [and] whites. They were… very mixed.”

Members of the urban Chinese communities in the Delta collectively came to view and portray themselves as an ethnic minority caught “in-between” the African American and Euro American communities. Largely disavowing any relations with Chinese-African American families, their opinions were mirrored by many members of local African American communities, who also shunned the families. This suggests that those who were really caught “in-between” were the inter-racial couples and their children. As a result, many of those involved remained isolated and their children often elected to hide their bi-racial ethnicities, save for the celebration of Chinese (Lunar) New Year and certain gravesite rituals. They either left the South altogether or were gradually absorbed back into the ethnic communities of their mothers, which further obscured their true identities.

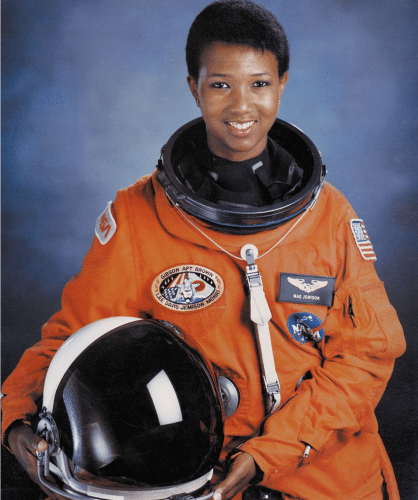

One year before the “Sardonic Sistah Says” blog about the Aaliyah-Jet Li kiss controversy was posted on-line, the first female African American astronaut and Decatur, Alabama native–Dr. Mae C. Jemison–had a DNA test. To her surprise, the results indicated that her maternal grandfather was Chinese.

Courtesy National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

Courtesy National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

By 2011, the historical trend of inter-racial marriage between the two groups had resurfaced on a global scale. An increasing frequency of inter-racial marriages among African women and overseas Chinese workers (as well as African merchants and Chinese women) was acknowledged by the Peoples Republic of China, along with an extension of citizenship to their offspring. There is now a “baby boom” for twenty-first century Afro-Chinese children who are bi-national, bi-cultural, and bi-lingual. They will most probably challenge existing concepts of ethnic and national identity and are expected to impact the global marketplace.

Since February 19, 2015 is Chinese (Lunar) New Year, the Cantonese salutation of “Gung Hei Fat Choi,” is appropriate as an introduction to your participation in the attendant celebrations. If you’re interested in learning more about this and other related topics, you can peruse the sources listed below.

Sources:

Please note that there is a large amount of material that is posted on-line about the Delta (Mississippi) Chinese but very little about inter-racial marriages between them and African American women. The best sources for this information are Cohen (1984), which includes photographs of Afro-Chinese families, and Loewen (1971).

China Whisper. “Chinese in Africa: Chinese Men Marry African Wi[ves].” https://www.chinawhisper.com/chinese-in-africa-chinese-men-marry-african-wife/ Accessed 16 2015

Cohen, Lucy M. Chinese in the Post-Civil War South: A People Without History. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1984.

Loewen, James W. The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1971.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “T.V. Preview: Famous Faces, DNA Reveal African-American Ancestry.” https://old.post-gazette.com/pg/06032/647467.stm Accessed February 14, 2015.

Quan, Robert Seto, and Julian B. Roebuck. Lotus Among the Magnolias: The Mississippi Chinese. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1982.

Sardonic Sistah Says. “No Sweet Lip for Asian Men.” https://rentec.wordpress.com/2007/05/29/no-sweet-lip-for-asian-men/ Accessed 06 February 2015.