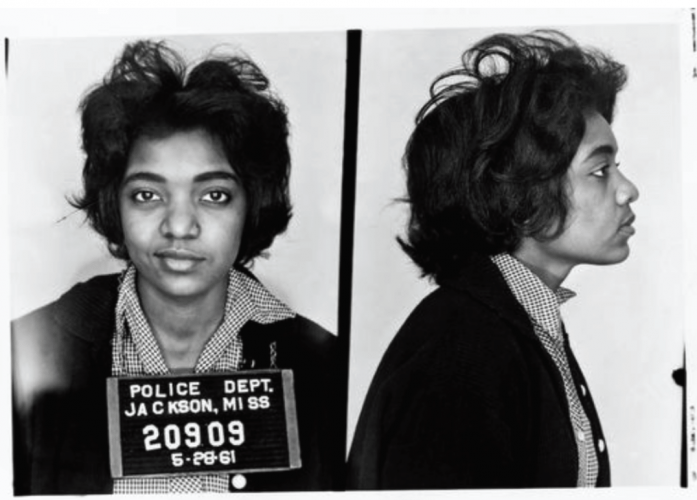

Freedom Rider Catherine Burks-Brooks, was born October 8, 1940 in Birmingham, Alabama. In 1961, she was a Senior at Tennessee State University, Nashville, Tennessee; active in the “Nashville Movement” as well as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee or “SNCC,” and volunteered to be a Freedom Rider in that year. Along with her husband, Paul Brooks, Catherine also registered black voters in Mississippi and served as the editor for the Mississippi Free Press from 1962-63. Photo Courtesy Tumbler.com.

Black Women’s History: Portrait of a “Freedom Rider”

By Stanley Solamillo

As we enter the presidential campaign of 2016, we should recall the efforts of all of the brave women and men who put their lives at risk so that we could vote freely in any election in the United States of America. Few of us today would be willing to take the risks that Catherine Burks-Brooks took at the age of twenty-one for an ideal that seemed impossible at the time—dismantling Southern Apartheid and re-enfranchising black voters. She was among over 500 black and white college and high school students who, along with adults, volunteered to become “Freedom Riders” in 1961 and who “after going South,” were subjected to insult and often attacked, then arrested and jailed.

Steely-eyed and smirking at the cameraman who took her mug shots at the Jackson, Mississippi Police Station (above), Brooks had been born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1940 and in 1961, was a senior at Tennessee State University, in Nashville. She became involved in the “Nashville Movement” (1960) that sponsored Civil Rights sit-ins, joined the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee or “SNCC” (1960) to integrate Nashville eating establishments, and then volunteered to become a “Freedom Rider.” Following her arrest in Jackson, Mississippi, she was held at Parchman Prison and then sent back to Tennessee.

Brooks married fellow Freedom Rider, Paul Brooks in August of that year and returned to Mississippi, where both of them registered black voters, and where she also served as the editor for Mississippi Free Press (1962-63). Brooks was in a riot at the Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station and endured the siege of the First Baptist Church in Montgomery. In later years, Brooks owned a jewelry boutique and worked as a social worker, teacher, and Avon cosmetics sales manager. Queried in a 2011 interview as to why she became a Freedom Rider in 1961, she responded that: “I knew what was happening was wrong. And I had an opportunity to do something about it…I didn’t want to die…but I didn’t have any fear of doing what I had to do.”

Suffrage rights for African Americans (males) in the South had actually been secured 91 years earlier after the end of the Civil War with the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment (1870), although free men of color had suffrage rights in six Northern States since the colonial period (1776-84), and African American women did not receive suffrage until 50 years later (1920).

While legalizing the rights of former slaves and free persons of color to vote in the South, the amendment disenfranchised former Confederates. In reaction to this as well as to the Thirteenth Amendment (1863) that had provided emancipation, and the Fourteenth Amendment (1867) that conferred citizenship, a wave of post-Civil War violence swept the South. In response, Congress passed three Reconstruction Acts in two years (1867, 1868) and placed the former Confederate states under the jurisdiction of a government that was administered by the U.S. military.

Each state was required to draft a new constitution that included the Fourteenth Amendment and was subject to approval by the Congress. During ten years of post-war Reconstruction (1867-77), black voters participated in elections and secured positions for 1,400 local black officials and 600 black state assembly members across the South.

Southern white racists especially resented blacks who assumed office in local and state governments—which included policeman and rural constables, sheriffs and police chiefs, magistrates and justices of the peace, mayors, secretaries of state, a state treasurer, a lieutenant governor and governor, in addition to a pair of state senators and sixteen congressmen.

The period of black suffrage and elected office was unfortunately brief and ultimately halted by the Supreme Court’s ruling in a case styled, Plessey v. Ferguson (1896). That decision upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation, which later became enshrined under the infamous “separate but equal” clause, and identified by the moniker of “Jim Crow.”

Since the end of Reconstruction, black suffrage was increasingly restricted by a plethora of legal instruments. They included: poll taxes, literacy tests, “Grandfather” clauses, suppressive election procedures, Black codes and enforced segregation, district gerrymandering, All-White primaries, restrictive eligibility requirements, and re-written state constitutions. In addition, any actions that represented citizenship for blacks were often aborted by physical intimidation and horrific violence that was carried out by racist Southern whites in mobs or as members of terror groups such as the Ku Klux Klan.

In the year that Pearl Harbor was bombed (1941), Thurgood Marshall, a Howard Law School graduate and legal director for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People or “NAACP” challenged the All-White primary in Texas in arguments made before the Supreme Court. The high court decided in his favor in 1944. Two other cases involving All-White primaries in the states of South Carolina (1955) and Georgia (1960) followed. Black voter registration increased somewhat after the Texas case but lacked the momentum necessary to impact the entire region.

Even the Supreme Court’s decision in the case styled Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that outlawed school segregation failed to substantially increase registration among Southern blacks. The Civil Rights Act (1957) was signed into law three years later but Southern states remained intransigent and their black populations remained dis-enfranchised because of continued harassment, intimidation, or worse.

The Congress on Racial Equality or “CORE,” an organization that had been formed in 1942 to protest discrimination in public accommodations, sponsored the first Freedom Ride (1947) and was followed by SNCC, that sent Freedom Rides from Washington, D.C. into the South fourteen years later (1961). SNCC (1960) had been organized around lunch counter demonstrations and also quietly fielded voter registration workers.

Brooks’ story as well as those of other SNCC participants was recorded for the PBS documentary titled, “American Experience: Freedom Riders” (2011). Two books—Eric Etheridge’s Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders (2008) and Holsaert, Prescod, and Noonan’s Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC (2012) have also been published.

Brooks appears to have ridden on at least two of sixty-four “Freedom Rides” that carried students and adults south of the Mason-Dixon line in private vehicles, chartered buses, or railroad passenger cars. Beginning with the CORE Freedom Ride that was dubbed the “Journey of Reconciliation” earlier in 1947 (April 9-23, 1947), the bulk of the Freedom Rides occurred in1961 and its participants included 521 college and high school students as well as adults.

Freedom Riders embarked on nine rides in May (May 4-May 30), nineteen in June (June 6-25, 1961), twenty-one in July (July 2-31), five in August (August 4-September 1), one in September (September 13), five in November (November 1-29), and three in December (December 1-10) of that year. The activism of Brooks and the other participants, both black and white, ultimately triumphed with the passage of the Voting Rights Act (1965).

In 2016, as the rhetoric from America’s right wing candidates flows unencumbered through the nation’s media outlets, it appears more and more evident that the speakers suffer from a “selective amnesia” that conveniently omits and distorts parts of our nation’s past. Those who have ancestors who survived slavery, lived through reconstruction, experienced Jim Crow segregation, and de-segregation in the South (as well as all who know better) are obligated, especially given the resurgence of hate (or blame) speech by individuals seeking public office, to be ever vigilant, vocal, and politically active. Please register, get informed, and vote!

Sources:

American Experience. “Freedom Riders: Threatened, Attacked, Jailed.” Public Broadcasting Service, 2011.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/freedomriders/rides

Barton, David. “The History of Black Voting Rights,” 2013.

https://www.freerepublic.com/focus/news/1072053/posts Accessed February 28, 2016

Global Nonviolent Action Database. “Nashville Students Sit-In for U.S. Civil Rights.” https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/nashville-students-sit-us-civil-rights-1960

Accessed February 28, 2016.

Salvatore, Susan Cianci, Neil Foley, Peter Iverson, and Steven F. Lawson. Washington, D.C.: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2007, revised 2009. https://www.nps.gov/nhl/learn/themes/CivilRights_VotingRights.pdf Accessed February 28, 2016.

Tumbler.com. “Catherine Burks-Brooks Photon” n.d. https://40.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_lkx1x0rS0p1qi1raio1_1280.jpg Accessed February 28, 2016.